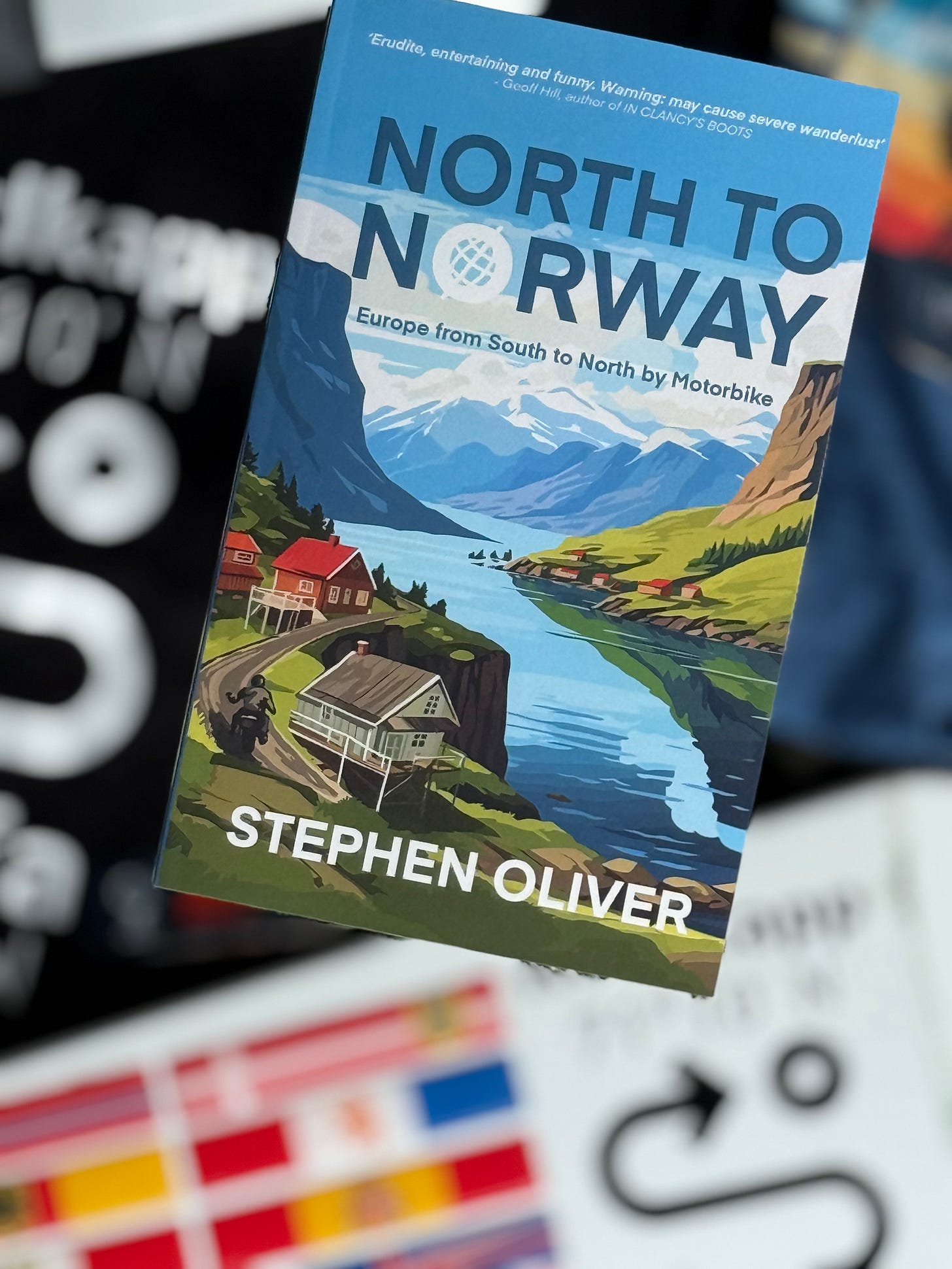

My new book ‘North to Norway’ is now out in paperback and e-book. It's a story as much about the joy of travel as about motorcycling. I’m sure I’ve mentioned it before! If you’re still wondering what all the fuss is about I thought a few excerpts over the next few weeks might give you a flavour of my writing and the adventures I recount in the book. I hope that you’ll want to buy the full version, available now on Amazon and in selected branches of Waterstones.

My way into Burgos was blocked by a posse of police cars and red and white barriers. People were everywhere, linking arms and laughing.

Though a Wednesday afternoon, everyone wore costumes, some in fancy dress, some in traditional outfits. Parking, usually a breeze, became a game of musical scooters in the chaos. I wedged myself and the bike backwards between two dust-covered relics outside a bustling bar. Stifling heat pressed down from the sky, the walls, the road. I shed my helmet and slung my jacket over my shoulder.

‘It is the Festival of San Pedro and San Pablo,’ chirped a girl in a smart blue blazer and white trousers, a flag held proudly in her hand.

‘Muy grande y muy importante,’ she added, lest I fail to appreciate the celebration’s significance.

I squeezed my way through the crowds, a near-impenetrable mass of inhabitants and visitors. This being Spain, of course, their annual fiesta was a week-long extravaganza. Los españoles love fiestas: religion meets history meets party town. Giant mannequins of kings, queens, knights, Sancho Panza and his donkey led by bands in traditional garb, paraded through the main square and the adjoining streets. It was a riot of noise and colour and joy. Balloons bobbed overhead, floral displays and ticker tape danced in the breeze. It was as though the whole city had been shaken up and its cork had just popped. It fizzed with excitement.

‘This is our first fiesta for two years,’ an attractive blonde with a red neckerchief and low-cut tee-shirt told me.

Curiously, she had a large penguin badge on her left breast, as did her gaggle of friends.

‘Yes,’ said another. ‘The pandemic cancelled it. Now we really celebrate.’

They both jiggled their chests at me and sashayed on through the crowds, penguin badges twinkling in the sunlight. I was enjoying the atmosphere and its flirtatious participants. I found a wall to lean on and enjoyed the floorshow for a bit longer. The bars were chokka, so a cooling drink was out of the question. I weaved my way out of the crowds and back to the bike, leaving them to their well-deserved celebrations, which I suspected were about to get messy.

As I accelerated away from Burgos, leaving the festive fun behind, the landscape morphed into a string of shanty villages, their roadside buildings a desolate mix of emptiness and decay. Faded Meubles signs hung askew on furniture warehouses like forlorn sentinels amidst the rural emptiness. I passed an old flour mill, the painted stucco walls peeling great chunks onto the baked earth and its rotten windows gaping limply with no sign of activity or life. This was a sign of how sparsely populated Spain truly is. Its population density is a mere third that of the UK, yet its landmass is twice as large. As in Britain, young people gravitate towards the bustling cities of Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia, leaving poorer regions like Castile and León to earn their nickname La España vacía (Emptied Spain).

A flash of movement caught my eye, a pair of storks roosting atop two mobile phone masts, their nests both creative and pragmatic. One, seemingly unfazed by my presence, loped off gracefully into the sky, our paths converging for a moment before it glided away towards a distant field. A short while later, a dust cloud erupted on the horizon, a swirling vortex obscuring the road ahead. As I neared the maelstrom, the culprit emerged: a tiny Fiat 500 bouncing along a farm track, its wheels churning the bone-dry earth. I coughed as dust seeped inside my helmet.

This was rugged country por excelencia.

Where Burgos had been lively, Aranda de Duero, the heart of the region's renowned wine production, was sleepy. I took a seat under a parasol. It was early afternoon and several locals in the Bar La Goleta had nodded off in the heat. One of them slipped gently off his stool onto the floor. He was a wrinkled old man in a scruffy check shirt and filthy sandals, as though he’d recently come into town off the fields. His mates, equally rustic, glanced over to where he lay, sprawled on the tiles, and decided to leave him to doze off his vino. They returned to their ritual lunchtime dominoes. La Goleta (schooner, in English) featured much maritime memorabilia, though the nearest sea was a good morning’s ride away.

Large piled plates of tooth-breaking torreznos, giant pork scratchings which dwarf our Black Country versions, dotted the bar. Resisting temptation, I downed a restorative coffee and bocadillo de jamón.

In Spanish I asked the proprietor for the Wi-Fi code.

‘Torreznos,’ he smiled, pointing to the curly golden pile of fried pigskin.

‘No, I meant what’s your Wi-Fi password, please?’ I repeated, fearing my Spanish was worse than I thought.

‘Es esso,’ (it’s that).

Should have guessed. “Scratchings” was the password. He raised a quizzical eyebrow at me and harrumphed.

With my iPhone connected, I opened the Paradors website. Run by the Spanish government, they're a collection of nearly 100 characterful hotels housed in historic buildings—castles, monasteries, even an old hospital. They showcase local cuisine, art and culture, offering an intimate way to experience the regions.

An overnight stay in the Segovia parador was my initial aim. With a click, my hopes were dashed. No room at that particular inn. Maybe my ad hoc travel philosophy was doomed to early failure? Not to be beaten, however, I tracked down a parador eleven kilometres away: Real Sitio de San Ildefonso. Tucked away high in the Sierra de Guadarrama, it was in an even more intriguing location and part of the Royal Palace of La Granja, built by Carlos III. A room was mine with the press of a button. How wonderful, this tech.

Aranda was full of bodegas and surrounded by vineyards. Enticing though the prospect of a little wine tasting was, I had a sacrosanct rule on the bike: no ride and imbibe. No space presented itself in which to stuff a bottle, not even a tiny one, so while Señor still snoozed on the floor and the dominoes clacked, I headed out of town before I could be tempted.

I had moved but a short way, crossing a bridge over the river, when a scrubby piece of brownfield caught my eye. Upon it was a semi-derelict long, low building with arched windows set high up on the walls which bore the painted words “Campo de prisoneros del Franquismo 1937–1939”. This needed no translation. It was a concentration camp, one of several hundred erected during the Civil War. In 2013 four mass graves with 129 bodies were uncovered, apparently executed by Nationalist forces. Some estimates hold that there are still over 120,000 victims of the war lying in ditches and other unmarked graves. Franco’s forgotten victims.

I walked pensively over to the building. No museum or even an information board. Nothing, nada. As with the piramide earlier in the day, it is still rare in Spain to find official recognition of such historical places. The 1977 Pacto del Olvido (Pact of Forgetting) helped restore democracy to Spain after Franco’s death. But it also meant that wounds still fester, unresolved injustices haunting successive generations, denying victims their dignity. It perplexed me why so little effort had been made to preserve the past and to contextualise the Civil War for future generations.

I carefully picked my way over the broken bricks and glass that littered the concrete floor of the camp, strewn with empty bottles, litter and used syringes. It was at least light inside. Had it been dark I would have gone no further. The malevolent air that seemed to seep out of its very bricks reminded me of Valle de Cuelgamuros (The Valley of the Fallen) outside Madrid that I had visited some years before. In this huge stone basilica and memorial Franco lay for forty-four years. Not only was it one of the most austere and sinister places I’d ever seen but it was catnip to a large group of ageing Francoists. They had waved their black and red Falangist flags in my face and chanted ‘Cara al Sol’ (Facing the Sun), the former unofficial anthem of nationalist Spain, as I had ridden my bike through its portal. It was one of the creepiest experiences I’ve ever had in Spain, ghosts of a dictator still echoing today.

I gunned the bike away from Aranda as soon as the speed limits allowed, happy to leave it behind. After the joy of Burgos, it seemed an oddly unsettling place.

© 2025 Stephen Oliver

If you’ve enjoyed this excerpt you can find the complete story in paperback and Kindle format on Amazon.